A History of Women in Higher Education

Credit: Image Credit: skynesher / E+ / Getty Images

Credit: Image Credit: skynesher / E+ / Getty Images- Until the 19th century, higher education effectively barred women.

- Slowly, the U.S. experienced a rise in women’s colleges and coed institutions.

- Most Ivy League schools refused to admit women and erected sister schools as a compromise.

- Despite women’s progress in higher ed, problems remain in pay equality, stereotypes, and anti-DEI efforts impacting women’s resources.

In 1636, approximately three decades after British settlers established their first permanent colonies on the coast of North America, the first American college, later named “Harvard College,” began educating students.

For the next 300 years, Harvard admitted only white men from prominent families. However, during that time, women were taking steps to turn the tide in their fight for a place at U.S. universities.

These days, most colleges and universities enroll women (except for a small handful of private, all-male institutions). But higher education’s coeducational transition wasn’t smooth. Generations of women faced pushback from male classmates, administrators, and others who framed their opposition as a defense of tradition.

But by the 1980s, women made up the majority of undergraduates, a position they continue to hold today. So, how did women break into higher education? With a lot of time and resilience.

Stay in the Know!

Subscribe to our weekly emails and get the latest college news and resources sent straight to your inbox!

Early Colleges Bar Women From Earning Degrees

The first European universities largely trained students for careers in the church. Theology, then dubbed the “queen of degrees,” ranked as the highest-status degree, followed by law and medicine. In medieval Europe, where universities in Oxford, Cambridge, Paris, and Bologna flourished, higher education was meant for men, as women couldn’t become priests, lawyers, or physicians.

When women began breaking their way into higher education, they often faced intense scrutiny. In 1672, Elena Lucrezia Cornaro Piscopia enrolled at the University of Padua to study theology. She impressed her instructors, even excelling in a public debate against three male intellectuals. But when Piscopia applied for her degree, the Catholic Church intervened. The institution declared that women should not earn theology degrees, barring Piscopia from graduating.

However, Piscopia’s allies pushed back, eventually helping her receive a Ph.D. in philosophy. Though Piscopia was the first woman to earn a Ph.D., her gender restricted her degree options, and the University of Padua did not award another doctorate to a woman for three centuries.

Like Piscopia, other women attended college classes, but most faced hurdles when it came time to graduate. Colleges might let women sit in on lectures, but only men could earn degrees.

Single-sex education was rooted in the idea that women didn’t need a degree to pursue socially acceptable roles like homemaker, mother, and domestic servant. As such, gender norms effectively excluded women from higher education for centuries.

The Rise of Coed Institutions and Women’s Colleges

The long exclusion of women from higher education gradually shifted in the 19th century. This change directly challenged Victorian notions of women’s roles, and many colleges resisted pressures to switch to a coed model.

Nineteenth-century women had two routes to higher education: They could enroll at coed institutions like Oberlin College or women’s colleges like Wesleyan College.

In 1837, just two years after opening its doors to African-American male students, Oberlin began admitting all women. Then, in 1862, the institution awarded a degree to Mary Jane Patterson, making her the first Black woman to earn a bachelor’s.

However, coed schools didn’t always treat male and female students equally. The year Oberlin first began admitting women, female students were dismissed from Monday classes to do male students’ laundry.

Women’s colleges offered another path to a degree. In 1836, Wesleyan became the world’s first college chartered to grant women degrees. Over the next several decades, other women’s colleges opened, including Barnard College, Bryn Mawr College, Wellesley College, and the first historically Black college for women, Spelman. In total, 50 women’s colleges opened in the U.S. between 1836 and 1875.

Nevertheless, even women’s colleges treated higher education for women as “dangerous experiments,” according to historian Helen Horowitz. Colleges for men modeled their campuses on the “academical villages” plan, in which men slept in dorms and crossed the quad to attend classes in various buildings.

In contrast, women’s colleges restricted their students’ freedom by modeling their campuses not on villages but on seminaries. Female students lived and studied in one building, an architectural choice intended to protect them from losing their virtue.

Trailblazers Defend Women’s Right to Education

The first female doctors, lawyers, and professors followed in the wake of colleges granting degrees to women.

In 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman in the U.S. to earn a doctor of medicine. On her journey to the medical profession, Blackwell received more than 10 rejection letters and a suggestion to disguise herself as a man to gain admission.

The only school that accepted her application, Geneva Medical College, believed her application to be a prank by a rival college.

Dozens more women physicians soon followed Blackwell’s path. In 1864, Rebecca Lee Crumpler became the first Black woman to graduate from medical school. She then moved to the South to use her medical knowledge to treat formerly enslaved people.

Colleges that admitted women also began hiring women as professors and administrators. Sarah Jane Woodson Early, one of the first Black women to attend college, used her Oberlin undergraduate training to become a professor at Wilberforce College, the first college founded by Black Americans. In 1858, Early wasn’t only the first Black woman college professor — she was also the first Black person to teach at a historically Black college or university.

Despite these breakthroughs, women continued to face barriers during and after their education. In the 1870s, the University of Edinburgh refused to grant medical degrees to seven women who spent years studying at the medical school.

The “Edinburgh Seven,” as they were called, faced professors who refused to teach them and male students who rioted when they sat for an anatomy exam. Eventually, several of the women moved abroad to become physicians. In 2019, the institution awarded the women honorary degrees on the 150th anniversary of their matriculation.

Sister Schools Try to Offer Women a Compromise

Many Ivy League schools did not admit women until the 1960s and 1970s. That being said, several paired up with “sister schools” that educated women. In 1879, Harvard created the “Harvard Annex” to educate women separately from its male undergraduates.

The impetus for the change came from Elizabeth Cary Agassiz, founder of the Women’s Education Association of Boston. In its records, the organization noted, “We were told not to disturb the present system of education which is the result of the experience and wisdom of the past.”

Pressure from women, however, encouraged Harvard to expand the annex. By the 1890s, Harvard had created Radcliffe College, a sister institution where women studied under Harvard professors.

In 2004, Harvard President Drew Faust called Radcliffe a “compromise between what women wanted and what Harvard would give them, as an alternative to the two prevailing models of coeducation and separate women’s institutions.”

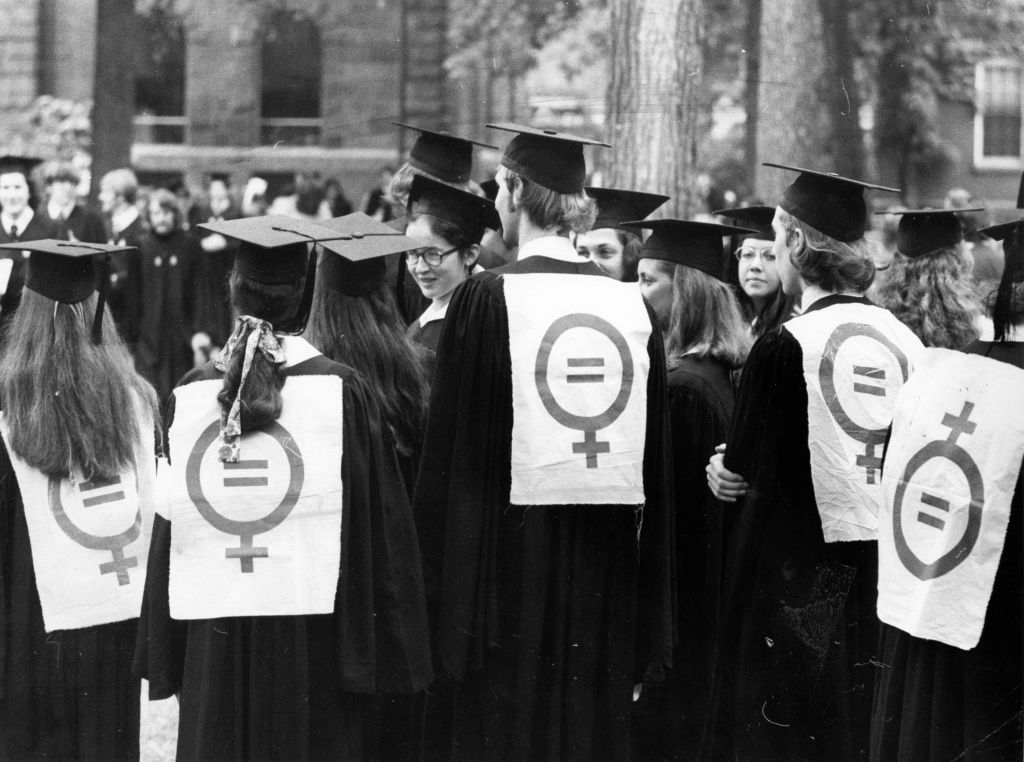

Image Credit: Geography Photos / Universal Images Group / Getty Images

Students at Radcliffe were separate but not quite equal to Harvard undergraduates. “Radcliffe College would educate women by contracting with individual Harvard faculty to provide instruction, would offer its own diplomas, to be countersigned by Harvard’s president, and would be subjected in academic matters to the supervision of ‘visitors’ from Harvard,” Faust explained.

By the 20th century, coed schools had become the norm rather than the exception. In 1880, 46% of four-year colleges and universities enrolled men and women, a number that jumped to 58% by 1900 and 64% just three and a half decades later.

In 1934, 7 in 10 undergraduates attended a coed institution. Stanford opened its doors in 1891 as a coed school, joined by the University of Chicago.

Even so, some schools held out well into the second half of the 20th century, insisting that the coed model would ruin the college experience.

The Ivy League Fights Back Against Coeducation

“For God’s sake, for Dartmouth’s sake, and for everyone’s sake, keep the damned women out,” wrote a Dartmouth College alum in 1970. Dartmouth undergrads even hung a “Better Dead Than Coed” banner from a dorm window.

These students weren’t alone in their desire to exclude women from Ivy League institutions. Outright misogyny marked much of the resistance to coeducation. One Princeton University alum complained, “What is all this nonsense about admitting women to Princeton? A good old-fashioned whore-house would be considerably more efficient, and much, much cheaper.”

Meanwhile, Yale University alumni worried about the “distracting” effect of women. “Gentlemen — let’s face it — charming as women are — they get to be a drag if you are forced to associate with them each and every day,” an alum wrote.

Image Credit: Boston Globe / Getty Images

Eventually, Princeton and Yale began admitting women in 1969, with Brown University following in 1971 and Dartmouth in 1972. The lone Ivy holdout, Columbia University, did not admit women until 1983. By contrast, Cornell University and the University of Pennsylvania had admitted women since 1870 and 1914, respectively.

So why did the Ivy League go coed? According to historian Nancy Weiss Malkiel, it wasn’t a result of the women’s movement, but rather university administrators’ desire to stay competitive. Increasingly, male students admitted to single-sex Ivy League schools declined their admission offers to attend coed institutions.

In 1967, Yale President Kingman Brewster Jr. said, “Our concern is not so much what Yale can do for women but what can women do for Yale.” The remark characterized women as a perk for male students instead of scholars who could benefit from an Ivy League education.

Columbia’s sister school, Barnard, declined a merger in 1975. This move ended up helping Columbia from a competitive standpoint: Its decision to admit women in 1983 led to a 56% jump in undergraduate applications. Later, Harvard and Radcliffe merged in 1999.

Women in Higher Education Today

In recent years, several institutions have pulled back from offering resources and support explicitly designated to women and other historically excluded communities in response to moves from conservative lawmakers and the Trump administration to dismantle diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs in higher education.

In January 2024, Florida International University and the University of North Florida eliminated their women’s centers to comply with a state ban on diversity, equity, and inclusion programs.

Other schools have dissolved and redistributed centers that support women and other historically excluded communities under broader academic centers.

In June 2024, the University of Utah announced it was closing three centers focused on underrepresented communities, including the Women’s Resource Center, and “reorganizing” their services into two new centralized centers to comply with a state law regulating diversity efforts on campus.

In September 2024, the University of Kansas “reallocated staff and resources” from women-centered initiatives, including the Emily Taylor Center for Women and Gender Equity, to the newly established KU Student Engagement Center.

And in February, the Georgia Tech Pride Alliance announced that the Women’s Resource Center, along with other initiatives for historically excluded students, would be proactively dissolved as a “calculated attempt at risk management” due to recent executive orders and state legislation and moved to the “Arts, Belonging, and Community Department.”

President Donald Trump’s executive order terminating DEI offices and positions also affected clubs for women and other underrepresented groups at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. The Washington Post reported that a dozen student clubs, including the West Point Society of Women Engineers chapter, were disbanded to comply with presidential executive orders.

In postsecondary institutions across the U.S., the class of 1982 included more women than men — the first time in U.S. history that women earned a more significant share of bachelor’s degrees than their male classmates. By the 2016-17 academic year, women earned 57% of bachelor’s degrees awarded in the country.

During the 2021-2022 academic year, women earned the majority of degrees at every level, comprising 63% of associate degrees, 59% of bachelor’s degrees, 63% of master’s degrees, and 57% of doctoral degrees.

Higher education has come a long way since women were excluded. Still, women’s success in higher education doesn’t always transfer outside of school. In 2022, women with at least a bachelor’s degree only earned 79% as much as men who were college graduates.

Why do men outearn women? In part, men are more likely to choose higher-paying majors. Around half of the wage gap comes from occupational choices — careers dominated by men typically pay more than those that employ more women.

Gender influences these choices, too, with persistent stereotypes discouraging women from science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields, for instance.

Within academia, women comprise only 47% of full-time faculty in the U.S. and 33% of tenured or tenure-track faculty. Women of color held an even smaller number of positions, with Black and Hispanic women making up 4% and 3% of full-time faculty, respectively.

The Future of Women in Higher Education

For centuries, women fought for access to higher education. Even though women make up a majority of college graduates in the 21st century, the fight isn’t over. Closing the gender pay gap, ending gendered ideas about majors, and supporting women in academia represent new frontiers in the battle for equality.

In an era where diversity efforts are rolling back, women will have to continue to work together to stand up against attempts to shut down and silence campus centers and initiatives that focus on women and other historically excluded communities.