How Dual Enrollment Can Rescue Colleges From the Enrollment Cliff

Credit: Carlos Barquero / Getty Images

Credit: Carlos Barquero / Getty Images- New data shows that almost 2.5 million high school students took dual enrollment courses in 2022-23.

- Dual enrollment figures have spiked over the past decade thanks to public investments.

- Participation in these programs is lower among underrepresented minority students.

- Students who take dual enrollment courses are more apt to attend and graduate from college.

New data from the Education Department shows that dual enrollment — high school students taking college classes — has grown substantially in recent years. Nationwide, more than 1 in 5 community college students attends high school.

Meanwhile, higher education enrollment numbers, while rebounding slowly, still fall well below figures from a dozen years ago, especially among community colleges. Today, about 61% of high school graduates attend college, down from nearly 70% in 2016.

And then there’s the really bad news: a demographic downturn in the number of traditional college-age youths beginning in 2025 and potentially extending for 15 years.

Could dual enrollment programs provide a solution for colleges and universities seeking to avoid tumbling down the enrollment cliff?

Explosive Growth of Dual Enrollment

Although it may seem like dual enrollment burst onto the scene only recently, it’s actually been in practice since the 1950s. But its popularity has indeed spiked over the past few years.

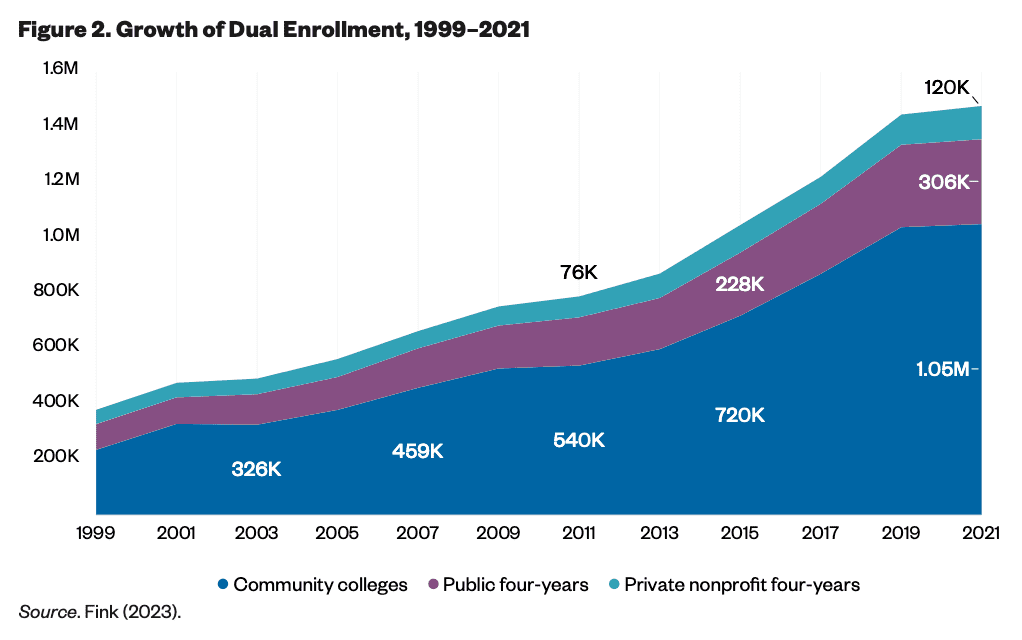

According to data from Teachers College at Columbia University, dual enrollment figures almost doubled from 2013-2021.

During the 2022-23 academic year, nearly 2.5 million high school students took a college course, according to new data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS).

Almost 72% of those students took courses at a community college, and dual enrollment students accounted for 21% of community college enrollments nationally.

An additional 445,000 high school students enrolled in courses at four-year institutions.

Nationwide, nearly one-third of high school graduates have taken at least one dual enrollment course.

Why has dual enrollment grown so rapidly in recent years? Several factors have conspired to spur participation, said John Fink, senior research associate and program lead at Teachers College’s Community College Research Center, which has produced a number of reports on this topic.

One is public policy. Several states have passed legislation expanding dual enrollment programs. In 2019 alone, Fink told BestColleges, states introduced more than 100 such bills.

“It has grown because states have been investing in it,” Fink said. “It’s a bipartisan issue, and very popular.”

Another reason is mission. Community colleges, in particular, are focused on providing students access to educational opportunities.

“What better place to partner with than your local high school to expand college access?” Fink said.

Finally, there’s a feeling of desperation among community colleges that have been losing students, as many high school graduates are either entering the job market or heading to four-year colleges instead. Dual enrollment programs offer a chance to grow enrollments thanks to a ready-made audience.

Community college leaders “reach out,” Fink said. “They make relationships and build partnerships. They can bring a couple hundred students into the auditorium and talk about this exciting opportunity to take free college courses in high school.”

Dual Enrollment as ‘Programs of Privilege’

The opportunities presented through dual enrollment manifest unevenly, Fink explained.

His research points out that, based on the latest IPEDS numbers, Black and Hispanic and Latino/a students are underrepresented in dual enrollment figures.

Although constituting 15% of public K-12 enrollments, Black students accounted for only 8% of dual enrollments in 2022-23 and were underrepresented in every state but Massachusetts, according to Fink’s research.

The situation was slightly better for Hispanic and Latino/a students, who made up 29% of the K-12 population but only 20% of dual enrollments. Still, Hispanic and Latino/a students enjoyed greater or equal representation in dual enrollment in 18 states.

Fink said dual enrollment is often referred to as “programs of privilege” because they tend to favor kids already on the college-bound track and leave behind those students who might benefit more from such an opportunity.

Barriers exist in several forms, Fink explained. One is transportation, assuming students need to travel to a college destination (most dual enrollment courses are either online or held at the high school). Eligibility standards can also impede access, especially if placement tests or high grade point averages are required.

Another is cost. Not every school district offers free dual enrollment courses, which can run students and families hundreds of dollars.

Then there’s a simple lack of availability. Many under-resourced schools don’t offer dual enrollment courses, or at least not a wide array of options.

Finally, even in such schools where dual enrollment exists, many students aren’t aware of the opportunities or believe they’re not designed for them.

Fink summarizes these challenges as “exclusionary policies, exclusionary practices, and exclusionary mindsets or attitudes.”

Yet he’s seen dual enrollment programs work in under-resourced communities and said they can be “a lever of access for students who are on the margins or maybe have totally written off college.”

“What we’ve seen at the places that have the best outcomes is that, when they’re done well, [dual enrollment programs] can really be transformative,” Fink said. “With just one course, they can give students a boost of like, ‘Oh, I am college material. I can do this.'”

Can Dual Enrollment Plug the Leaky College Pipeline?

Given dual enrollment’s rise in popularity, does it hold promise for colleges looking to regain lost enrollments and mitigate the effects of the demographic cliff?

Even though college enrollments rebounded last spring, figures still fall well below pre-pandemic totals. And numbers from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, which touted a 2.5% year-over-year increase in spring enrollments, can be misleading.

That’s because its totals include dual enrollment students. Removing that line item from the report reduces the overall growth from 2.5% to 1.9%.

Counting high school students who aren’t enrolled but are taking only a course or two, sometimes taught by high school teachers and not college faculty, artificially inflates overall enrollment figures and creates a false sense of optimism that more students are opting for college.

Starting next year, that optimism will wane even further when this nation begins losing more than half-a-million college-age students over the ensuing four years.

Yet there’s hope in the form of dual enrollment, Fink believes. Studies have shown, after all, that students who take dual enrollment courses are more likely to attend college and earn degrees.

“We can’t afford not to do this because we’re losing so many high school students every year at the point of graduation,” Fink said. “They’re just not coming into higher education. So if we can do dual enrollment very well … it’s going to be worth it because you’re growing the supply of future students.”

Fair enough, but if these dual enrollment students were going to attend college anyway, as the “programs of privilege” concept suggests, then they’re not increasing the pipeline of prospective students. Instead, the answer lies in the form of students for whom dual enrollment will tip the balance in favor of college.

Fink suggests states, schools, and colleges examine ways to engage that “next third” of students in dual enrollment, investing in programs that promise high dividends based on past returns.

“Now the work is to cast a wider net and make sure everyone’s included,” he said. “And if we want to keep growing, we need to focus on the folks in the communities who are underrepresented because that’s where the room for growth is.”

Doing so requires a more strategic and thoughtful approach, Fink said. Too often, schools provide “random acts” of dual enrollment, haphazard and limited efforts resulting in a mishmash of courses devoid of any clear pathway for students.

A better approach would be to offer more career and technical education courses that clearly align with degree programs at both community colleges and four-year schools. These courses would complement the usual array of gen ed offerings designed for most college-bound students.

Absent a more focused effort to engage low-income, first-generation, and underrepresented minority students, dual enrollment might even exacerbate existing racial and income gaps, Fink says.

“Through the ‘programs of privilege’ approach, or the ‘random acts’ approach to dual enrollment, it has really replicated existing inequities and expanded gaps,” he said.

“But that hasn’t happened in every community, and where there is a clear, intentional, and strategic approach to dual enrollment that’s focused on equity and on expanding college access, we see that it actually can close gaps.”

If done right, dual enrollment has “great potential” to solve the enrollment cliff problem colleges face, Fink believes.

“There’s just so much talent wasted even among our shrinking populations,” he said, “and there’s a lot of room for improvement to address these declining enrollment trends.”