College Completion Programs Yield Impressive Returns. Who Will Invest in Them?

Credit: showqdf

Credit: showqdf- Two out of every five college students likely won’t graduate within six years of enrolling.

- Hurdles including costs, family responsibilities, and lack of engagement can lead to dropouts.

- Many programs have proven that universities can help students overcome these obstacles.

Two years after arriving in the U.S., Obed Gyedu Larbi took the next step in his pursuit of the American dream and enrolled in his local community college.

He had no family or friend experiences to draw from to help prepare him, as all his loved ones remained in his home country of Ghana. He had no real expectation for the kind of workload involved or how to navigate higher education bureaucracy. He didn’t even have reliable transportation to get him between home, work, and school.

Looking back at that time in 2017, Larbi told BestColleges he isn’t sure how he would have managed without his school’s dedicated program for college retention and completion.

He was enrolled at Bronx Community College, a school in the City University of New York (CUNY) system that has pioneered one of the premier student retention programs in the country. Its 15-year-old Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP) has helped inspire a growing movement across higher education in America to help students complete their degrees.

While enrollment increases were the focus throughout most of higher education’s history, Third Way senior education policy advisor Michelle Dimino told BestColleges that an increasing number of colleges now prioritize ensuring the students they enroll actually get to cross the graduation stage in a timely manner.

“For a long time, we really focused on increasing access to college,” she said. “We’re at a point where we’ve done a really good job in increasing access. Now is an important time to make sure [students] are getting through.”

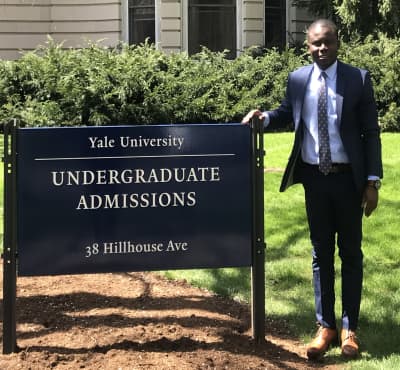

Photo courtesy of Obed Gyedu Larbi

Students like Larbi now get to reap the rewards of the increased focus on college completion.

He earned an associate degree in accounting from Bronx Community College and was accepted at Yale University, where he’s pursuing a political science degree. He credits CUNY’s ASAP advising network for enabling his leap forward.

“The fact that you have an advisor that is specific for you that makes sure that you get all your things together was something I really appreciated,” Larbi said. “For someone to care about you that much… that was something that really stuck out to me and helped me.”

Data Reveals Divide Impacting Students Of Color

At first glance, the data on college completion is encouraging. However, progress hasn’t been universal, and a deeper dive into the data shows marginalized students aren’t enjoying the same gains.

The national six-year completion rate for the most recent cohort of students grew to 62.2%, compared to 61% the previous year, according to data from the National Student Clearinghouse. Completion rates have risen nationally year over year since the 2009 cohort started their schooling.

However, community colleges and for-profit institutions continue to lag behind the national average, and both these types of schools enroll large proportions of racial minority and low-income students. The Institute for Higher Education Policy (IHEP) found that Black, Indigenous, Latino/a, and underrepresented AAPI students are 30% more likely than white students to temporarily withdraw from — or “stop out” of — college.

Ed Venit, managing director at student success research firm EAB, told BestColleges that data suggests student engagement and completion are closely linked.

According to the National Survey of Student Engagement conducted just before the COVID-19 pandemic, 23% of first-year students said they did not feel like they were part of their campus community. Those respondents were more than four times more likely to say they did not intend to return for a second year compared to those who said they did feel like they belonged.

The pandemic has only exacerbated this sense of not belonging among students, he added.

“If we assume from past data that engagement and socialization are important for graduation, and that engagement is not happening right now,” Venit said, “then we should be concerned.”

It’s part of the reason many student success programs don’t only focus on financial aid and emergency grants. They also highlight initiatives like counseling, childcare access, and community building. Larbi said it was advising that made the biggest impact on his ability to graduate.

A Decade of Data Shows College Completion Programs Work

Many of the more established college completion programs have been around for nearly a decade, providing advocates and policymakers data showing their success.

For example, ASAP achieved a high success rate quickly. CUNY reported that ASAP students (40.1%) graduate within three years of enrolling at nearly double the rates of the system’s non-ASAP students (21.8%).

Following those signs of promise, three community colleges in Ohio sought to replicate the program. Students enrolled in one of these programs earned a degree within three years 34.8% of the time, while control group students earned a degree just 19.2% of the time.

Program enrollees also tended to earn more college-level credits after three years than others.

Think tank Third Way extrapolated this data to estimate how many more students would graduate if ASAP were replicated nationwide. Its analysis found that over 10 years there would be 1.56 million more associate degree holders than current trends predict.

ASAP isn’t the only proven model; individual colleges are implementing their own wrap-around guidance programs that have increased retention rates.

William Latham, chief student development and success officer at the University of the District of Columbia, told BestColleges that peer-to-peer guidance counseling is the key to increasing graduation rates because it helps students who are most vulnerable to dropping out: people from historically excluded backgrounds.

“Oftentimes you see students come into institutions that had never seen bureaucracy like this,” he said. “We usually drop these students in and say, ‘Good luck.'”

UDC’s program instead creates a connection between two students so that new enrollees have a point person for any college-related question. Not only does this prevent bureaucratic issues from impeding progress, Latham said, but it also means new students feel more engaged with their university.

Latham reports that UDC’s retention rate grew 15 percentage points over the past four years, which is when the peer-to-peer advising program started.

The bottom line: “Students that are more engaged in college persist,” Latham said.

Programs Also Help Drop-Outs Become Graduates

While programs like CUNY’s ASAP focus on keeping students enrolled, other institutions and organizations are turning their attention to those who have already dropped out.

The Institute of Higher Education has made it a priority to lure students back to school for over a decade. Its latest effort, Degrees When Due, found quick success.

According to a May assessment of the program, it identified over 170,000 former students at nearly 200 institutions as “near completers,” meaning they had already completed two years of coursework without a degree. Of that number, approximately 10,700 earned a degree thanks to the program and another 3,000 are on track to do so.

Leanne Davis, formerly the associate director of research and policy at IHEP, told BestColleges that one takeaway from the pilot is that success in this arena is slow. Institutional adjustments drive the most change, but also take the longest time to implement.

“We’re hoping to not just see the impact on completion rates…but a lasting impact at the institutional level.”

“We’re hoping to not just see the impact on completion rates,” she said, “but a lasting impact at the institutional level.”

The other reason success is slow is that the first step in the process — identifying “near completers” — is often the most time-consuming. It requires every participating community college to conduct a degree audit to identify which students fit the definition.

Kate Mahar, dean of innovation and strategic initiatives at Shasta College in California, told BestColleges that two employees sifted through transcripts by hand to identify students close to a degree that the college could contact.

“It’s slow up front, but once you start seeing the trends, it becomes easier to spot [these students],” Mahar said.

Buffy Tanner, director of innovation and special projects at Shasta College, said that the laborious degree auditing process was important because it revealed to administrators that one computer literacy course was a common reason many students didn’t qualify for an associate degree. If the school could remove this hurdle, 79 of the 400 stopped-out students identified could graduate immediately.

It was a problem counselors knew anecdotally, she said, but having hard data helped convince leadership to make changes to the required coursework.

“Immediately our whole campus culture changed,” Mahar said. “There was no resistance after that.”

Now, only some programs require this computer literacy course. Tanner and Mahar looked into the high school transcripts of past students who missed the requirement and found that 85% had taken a similar high school course, so they got to graduate. The remainder could take a free hour-long exam to prove proficiency and earn a degree.

Trickle-Down Effect: Higher Completion Rates

While the work of Degrees When Due isn’t focused on increasing six-year completion rates, its work has a trickle-down effect.

For example, now that the computer literacy course isn’t a requirement for most programs at Shasta College, Mahar and Tanner expect future students will be able to graduate on time without being hung up on the course.

Davis said such lessons have become commonplace at participating institutions — they all discover their own problems through audits, but once they find them, they can fix the problem for future students.

Another common issue identified by participating institutions, she said, was applying for graduation. Quite simply, many students don’t realize they have to apply to graduate. They often assume that once they meet the requirements, they get a degree automatically, but that’s generally not the case.

Once schools realized how many students should have degrees but don’t — nearly 10%, Davis said — they changed their respective processes. Many participating institutions now automatically award associate degrees or have an opt-out option for those that don’t want the degree and plan to transfer to a four-year university, Davis said.

“It’s not low-hanging fruit to re-engage students. It takes a lot of work, dedication, and investment to prioritize serving this population.”

The hope, she added, is that such lessons can be applied at schools that aren’t part of the Degrees When Due pilot.

“Now our goal is to say, ‘Here are the larger system-level policy recommendations we can make’ for systems or for states that are interested in improving their completion outcomes,” she said.

Despite the challenges, Davis believes more colleges will realize that identifying and attracting “near completers” back to their institutions can boost graduation numbers.

“It’s not low-hanging fruit to re-engage students. It takes a lot of work, dedication, and investment to prioritize serving this population,” Davis said. “This notion of serving students with some college [experience] and working learners is not going away, and it’s also not a quick fix.”

Who Will Invest in Proven Programs?

Programs like ASAP and Degrees When Due are expensive, which is a primary reason more schools aren’t replicating them.

New York state and municipalities pumped significant funds into CUNY’s ASAP, according to an analysis from New America: nearly $80 million annually to support approximately 25,000 students.

Meanwhile, philanthropic organizations helped fund ASAP’s replication in three Ohio community colleges. However, due to the high costs associated, only Lorain County Community College (LCCC) continued offering ASAP beyond the pilot years, despite all three mirroring ASAP’s success.

LCCC’s program costs approximately $2,500 per student, according to New America. The school offsets some of that cost with the additional Pell Grant funds it generates from more low-income enrollees, but it has failed to secure continued funds from the state government.

It’s not just ASAP that’s expensive. The Institute for College Access and Success found that the average cost of an evidence-based retention program costs between $1,800 and $8,000 per student.

“The average cost of an evidence-based retention program costs between $1,800 and $8,000 per student.”

These programs have sizable benefits for students, however.

An analysis of Project QUEST in Texas followed participants 11 years after enrollment and compared their earnings to a control group of students who didn’t participate in QUEST. Within two years QUEST students were outearning the control group, and that trend continued throughout the duration of the study.

QUEST cost approximately $12,450 per student. Even with this cost, average net earnings

exceeded average costs by over $17,400 per student.

Success stories such as Larbi’s haven’t been enough to move the federal government to make big investments in programs like ASAP. President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better legislation proposed a $500 million grant program to invest in the College Completion Fund. However, that legislation has stalled in Congress and appears to have died completely heading into midterm elections.

Incremental investments are moving through Washington, though. The recently passed 2022 budget sets aside just $5 million for postsecondary student success programs, and Biden’s proposed 2023 budget included $110 million for these programs.

Dimino of Third Way said the decline in proposed funds is significant, but considering the federal government has never invested in these programs before, any investment is a good sign.

Venit of EAB added that with decreased enrollment and student engagement due to the pandemic, retention and re-enrollment programs are now more important than ever.

“If we don’t do these things,” he said, “we will have lost those students and we will have lost the gains we’ve made.”