Changing Demographics Will Impact Higher Education for Years

Credit: SDI Productions / E+ / Getty Images

Credit: SDI Productions / E+ / Getty Images- A new study shows the population of high school graduates shrinking over the next 16 years.

- Estimates suggest there will be 13% fewer graduates in 2041 than in 2025.

- Population losses will be uneven based on race and ethnicity and by region.

- Colleges should make necessary changes in anticipation of enrollment challenges.

Higher education is in for a bumpy ride over the next 16 years thanks to a shrinking pool of potential students.

As university leaders head into the second half of the decade, they’re about to encounter the notorious enrollment cliff, a demographic phenomenon heralding a drop in college-age students stemming from fewer births during the Great Recession.

If that’s not bad enough, the news gets even worse: New projections suggest the decline will continue into the 2040s and will be steeper than originally projected. Layer upon that the longstanding downward trend in college attendance, and it constitutes a recipe for disaster for many colleges.

Yet “demography is not destiny,” claims a new report warning the industry to prepare now … or else.

Demographic Declines Worse Than Projected

In its new report, “Knocking at the College Door,” the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) offers new data about the demographic challenges higher education will face in the coming years.

Beginning in 2025, the number of high school graduates will steadily decline until 2041. Despite periods of “relative stability” from 2028-2035, the overall trend is a “downward slope” resulting in 13% fewer graduates in 2041 than in 2025.

It’s important to note that the report concentrates on high school graduates, not birth rates, though the authors demonstrate a strong correlation between the two trends, as graduation rates have held fairly steady over the past decade.

Demographic studies focused on birth rates reach similar statistical conclusions. A recent Census Bureau projection suggests that beginning in 2034, the number of 18-year-olds will precipitously decrease, dropping from 4.2 million in 2034 to 3.8 million in 2039.

Some have referred to this period as the “second enrollment cliff.”

What makes these new projections worse is the downstream effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, the WICHE report points out. Again, by focusing on graduation figures, the report estimates a decline based on decreased enrollment in earlier grades resulting from the pandemic.

How has this transpired? Although the report acknowledges that “the available information does not provide clear conclusions about what has happened to these students,” it speculates that more families opted for homeschooling during the pandemic and that fewer families immigrated to the U.S. in those years.

Complicating this scenario is the downward trend in enrollment over the past dozen years, even accounting for recent upticks. In 2010 just over 70% of high school graduates went on to college. By 2022, that figure had dropped to 62%.

None of this adds up to a rosy future for higher education.

“In short, the answer is that, yes, leaders and decision-makers in postsecondary education, as well as the industries and economies that rely on the skills and abilities developed through higher education programs, should be concerned,” the report concludes.

Winners and Losers in the Demographic Sweepstakes

The news isn’t all bad for higher ed leaders, depending on where they’re located.

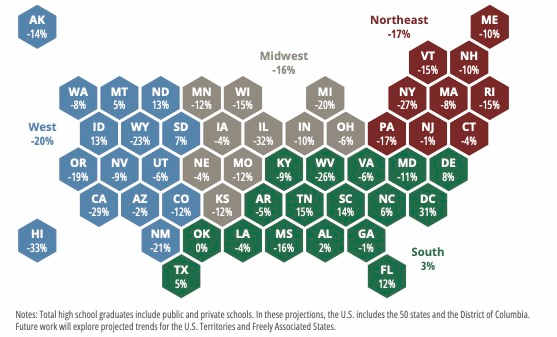

Overall, from 2023-2041, 38 states are projected to experience a decline in the number of high school graduates. But a dozen states and the District of Columbia will actually see an increase.

Projected Percent Change in High School Graduates, 2023 to 2041

Seven states will have a decrease greater than 20%, the report says. Five states — California, Illinois, Michigan, New York, and Pennsylvania — will account for three-quarters of the expected drop over that period.

States in the West will suffer a decrease of about 20% during that span, while the Northeast (17%) and Midwest (16%) will also lose a considerable number of students.

Meanwhile, the South will experience a growth rate of 2-3%, the report notes, as the rich get richer. A recent Wall Street Journal analysis found that the number of Northerners attending public universities in the South increased by 84% over the past two decades, climbing 30% from 2018-2022 alone.

In terms of race and ethnicity, the number of white students will decrease by 26% by 2041, constituting only 39% of the graduating class that year. Black representation will also decrease, dropping from 14% in 2023 to 12% in 2041.

At the same time, the Latino/a student population will increase from 27% of the class of 2023 to 36% of the class of 2041, while the number of Asian graduates is projected to increase from 206,000 in 2023 to 213,000 in 2034.

Demography Is Not Destiny

What can higher education leaders do to combat the effects of this demographic cliff? The report’s final section offers some thoughts and suggestions.

One answer is to improve matriculation rates. A larger percentage of students attending college will offset a loss in graduation numbers. But matriculation figures have been heading in the wrong direction, so achieving this goal would constitute a seismic shift.

To counter the decline, the report estimates, the matriculation percentage would have to increase to 68%, a hefty stretch from the current 61%.

That said, the report also notes that between 1990 and 2005, the matriculation percentage rose from 60% to 68%, so it’s not without precedent.

Another solution is to improve retention rates, which won’t affect the number of students entering college but will increase overall headcount. The six-year completion rate has risen to 61.1%, an all-time high, so this figure is trending in the right direction, but when only 3 in 5 students graduate, there might be room for improvement.

Other suggestions include demystifying the college-going process, especially for first-generation students; enrolling more adults; and offering alternative credentials linked to high-demand careers.

Finally, cost remains a barrier for many students, so curbing tuition increases and reducing related expenses should top the list for colleges and state governments, the report recommends.

Colleges hoping not to fall victim to the destiny forecasted by demographic projections must do a better job of attracting and retaining students who today are opting for the job market and other forms of training.

“If higher education collectively cannot ensure its relevancy, demonstrate its value to students, and improve student outcomes like retention and completion,” the report suggests, “these demographic trends will exacerbate the existing enrollment trends, leading to substantial drops in the number of students, increased workforce shortages, and fundamental financial difficulties for many tuition-dependent institutions.”