Here’s What Students Should Know About Gender Inequity in Selective College Admissions

Credit: Boston Globe / Getty Images

Credit: Boston Globe / Getty Images- Women outnumber men in higher education, accounting for about 60% of enrollments.

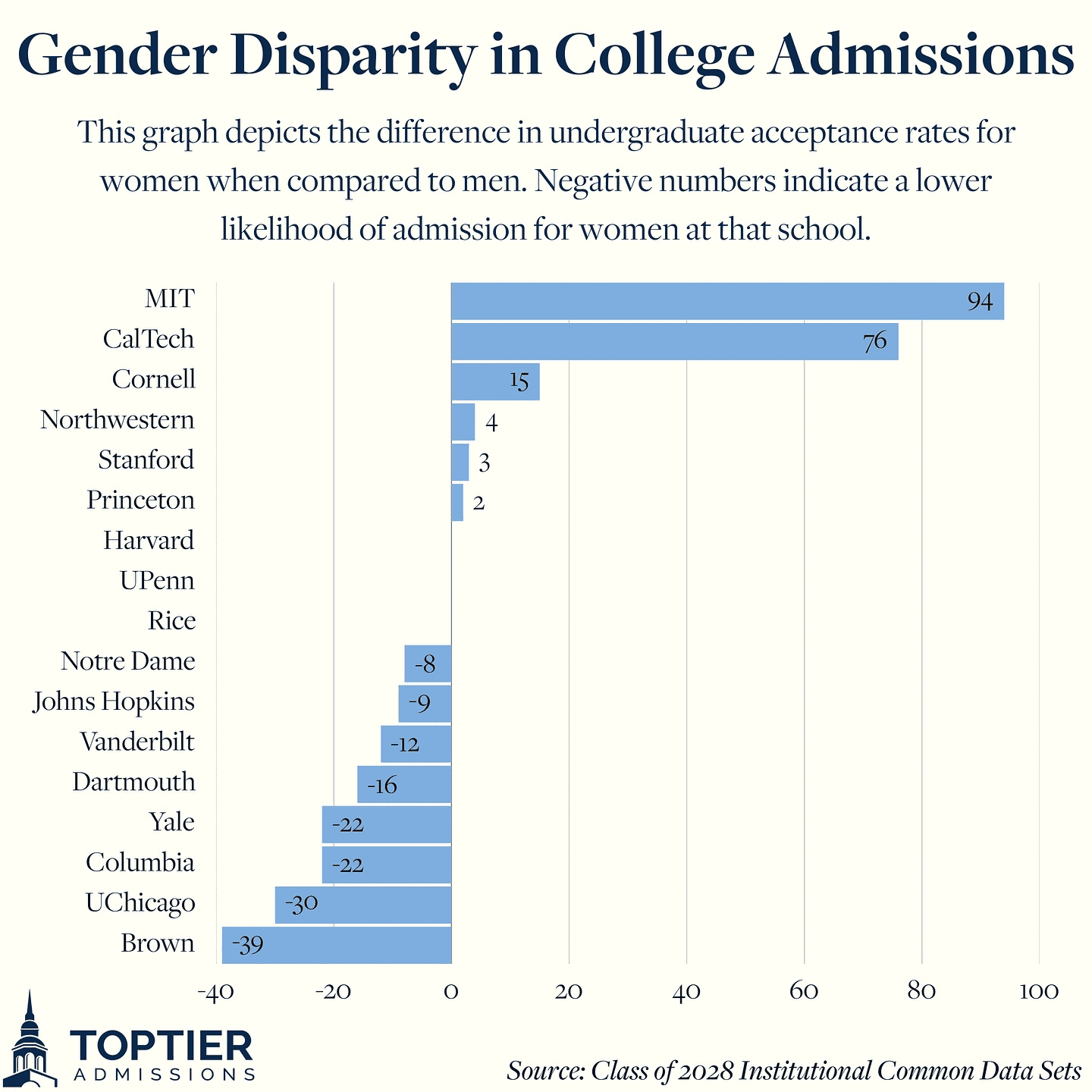

- Some elite colleges feature higher acceptance rates for men than women given the imbalanced applicant pools.

- Conversely, top tech-related universities and some business schools favor women.

- Not all highly selective schools achieve a gender balance despite large applicant pools and strong yields.

In recent years, the conversation around selective college admissions has centered on race, thanks largely to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2023 decision banning affirmative action.

At the same time, another form of preferential treatment has flown largely under the radar, comparatively speaking. Many students know it exists, admissions experts say, but they don’t understand its pervasiveness or severity.

We’re talking about admissions advantages based on gender.

Affirmative Action for Men

The prevailing evidence surrounding gender-based preferences is that they tend to favor men.

That’s because a significant gender gap has emerged across higher education. For decades, women have increasingly outpaced men in college attendance. In fact, the last year men outnumbered women in higher education was 1978.

The pandemic served only to widen that chasm, and, as of 2022, women constituted about 60% of college enrollments.

Women are also more likely to earn their degrees. Men finish college within four years at a rate 10 percentage points behind the rate for women.

Richard Reeves, author of “Of Boys and Men,” noted this completion gap in a February episode of the “Future U” podcast, unpacking the various reasons why men trail women in “to” and “through” college-going rates.

So colleges have a “men problem.” As such, to manifest a more equal gender balance on campus, some colleges favor male applicants. Simply being male can amount to a “thumb on the scale for men,” a 2023 New York Times Magazine exposé revealed.

When an attempt to rebalance the gender profile meets an applicant pool consisting largely of women, who on average apply to more schools than men, the result can be acceptance rates tipped heavily in favor of males.

This phenomenon occurs across U.S. higher education, but is it happening at highly selective universities, where huge applicant pools and strong yield rates enable institutions to more carefully shape an incoming class?

At some schools, yes. Men applying to Brown University have a 39% better chance of getting admitted than women. At the University of Chicago, that advantage is 30%.

Maria Laskaris, a senior private counselor at Top Tier Admissions, has been aware of this situation for some time.

She attended Dartmouth College around the time the school went co-ed and ramped up its efforts to attract women. Later, when Laskaris was an admissions director at Dartmouth, the college was experiencing the “last vestiges of change” from an all-male institution and still trying to recruit more female applicants.

A recent conversation with a high-achieving student prompted Laskaris to dig into data submitted to the Common Data Set to determine just how much of an advantage one’s gender confers.

“It’s what I had suspected — that there are schools very aggressively shaping the way they admit students in order to meet their enrollment objectives, which in this case is trying to get as close as possible to a 50-50 ratio of men and women,” Laskaris told BestColleges.

Courtesy of Top Tier Admissions

Let’s take a closer look at Brown, where the male bias is rather pronounced.

In fall 2023, 19,666 men applied, and 31,650 women applied. The acceptance rate for men was 6.8%; for women, it was 4.2%. Both genders yielded at roughly the same rate (around 63%), resulting in an incoming class of 846 men and 849 women.

Thus from an applicant pool reflecting roughly 61% more women, Brown enrolled a class almost identical in gender representation (leaving aside nonbinary students, whom Brown doesn’t include in Common Data Set figures).

Laskaris believes such parity results from conscious decisions to favor men during the admissions process.

“I do think at some level there is a conversation that says, ‘We want to get to as close to gender parity as we can. We don’t have it in our applicant pool,'” she said. “So yeah, some shaping is done of the pool that’s admitted because otherwise, the numbers wouldn’t be that precise.”

Is there any chance the 2023 cycle at Brown was an aberration? Not really. In fall 2022, men were accepted at a rate of 6.7%, compared to 4% for women, giving men a 40% better chance of getting in.

For the 2021 cycle, Brown accepted men at a rate of 7.1% and women at 4.5% — an almost 37% difference. That year’s incoming class consisted of 859 men and 846 women.

Brown isn’t the only school giving an advantage to men. At UChicago in 2023-24, men were accepted at a rate of 5.7%, compared to 4% for women.

And at Swarthmore College, the 2023 cycle featured 8,296 female and 5,991 male applicants, with 6% of women and 8.2% of men being accepted — a 37% difference. The incoming class comprised 208 men and 207 women.

Laskaris said these schools are “actively practicing affirmative action for men so as to not end up with a class that’s too heavily female.”

At some institutions, Laskaris found, there’s no admissions advantage based on gender. Schools such as Harvard University, the University of Pennsylvania, and Rice University reflect similar acceptance rates for men and women.

That doesn’t mean the incoming classes are always balanced. At Harvard, for example, the 2023 applicant pool included 30,636 women and 26,301 men. Both groups were accepted at the rate of around 3.4% and yielded similarly at 83.7%, resulting in an incoming class of 765 men and 880 women.

Essentially the same results occurred in the 2022 and 2021 cycles.

At Tulane University, “Exhibit A” in The New York Times Magazine feature, female applicants far outnumbered males (20,864 vs. 11,129) in 2022, yielding a class of 619 men and 1,224 women.

For UChicago’s 2023 cycle, men were admitted at a 42.5% greater rate, leading to an incoming class with 19% more men than women.

Are such gender preferences more “dirty little secrets” universities would prefer to remain out of the public eye given the inherent unfairness cooked into the process?

“I don’t know how forthcoming [universities] would be about putting extra fingers on the scale,” Laskaris said, “but it’s clear from the data that they are.”

Affirmative Action for Women

What remains more under the radar is the advantage women have in admissions at certain selective institutions.

As Laskaris’ graphic shows, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), women had a whopping 94% better chance of admission than men in the 2023 cycle. At the California Institute of Technology, that advantage was 76%.

In fact, in the 2021 cycle at MIT, the 21,672 male applicants were admitted at a rate of 3%, while the 11,568 women who applied were admitted at a rate of 6%, meaning women had twice as good a chance of admission, all else equal, than men. That year, 603 men and 573 women enrolled.

At Harvey Mudd College, another tech-focused school, women had an incredible 147% better chance of admission than men in the 2024 cycle, generating an incoming class of 115 men and 116 women.

Yet at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, even though the 2023 applicant pool included twice as many men as women, the acceptance rate was equal for both genders, resulting in a class of 1,035 men and 517 women.

Clearly, the demand for spots at tech schools is greater among men, and achieving a gender balance, or something close to it — assuming that’s an institutional goal — requires tipping the admissions balance in favor of women.

The other imperative is addressing the shortage of women in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) majors and careers. Nationwide, women earn 24% of bachelor’s degrees in engineering, 21% of computer science degrees, and 24% of physics degrees.

Jayson Weingarten, a college admissions consultant with Ivy Coach and a former admissions officer at the University of Pennsylvania, told BestColleges universities will favor certain genders based on majors. He saw this occur at Penn, where the engineering school skews male and the nursing school skews female.

“If you look at the enrollment of the undergraduate nursing program, men are going to stand out,” he said. “They need to find more men to be nurses just like they need to find more women to be engineers.”

Slight advantages exist among some business programs as well, where women make up about 43% of undergraduates, according to a Poets & Quants analysis.

At Babson College, an undergraduate business school, the 2023 admissions pool featured 4,977 men and 3,018 women. Even though women (25%) were admitted at a greater rate than men (16%), men (352) still outnumbered women (274) in the incoming class.

Similarly, at rival Bentley University, the 2023 cycle had 6,213 male and 4,268 female applicants. Fifty-two percent of women were accepted, along with 46% of men, yet the result was a class of 664 men and 456 women.

Weingarten calls this gender advantage a “tip factor” in selective college admissions, a theoretical tiebreaker determining the fate of one applicant versus another.

“It’s rarely a tie, but in the cases where you could construct one, the tie will go to the student who has that tip factor,” he said.

Making Admissions Decisions Based on Gender

In their line of work, Laskaris and Weingarten often advise students to consider selective colleges where they might enjoy a gender advantage.

“If you’re a wonderfully bright, capable, amazing girl and you’re indifferent between going to Brown or Penn, you probably should apply to Penn strategically,” Weingarten said. “It’s going to be that much easier to get into Penn.”

While such disadvantages for women at Brown may not come as a surprise to some students, the severity of that disadvantage often does, Laskaris said.

“A lot of young women who are very interested in going to Brown can see it in their own schools and in their own peer groups,” she said. “They’ll report back to me, ‘Wow, no girls from my school have gotten in. Brown only takes guys from my high school.”

Still, she advises them, “If you want to go for Brown, let’s go for it. But you need to know it’s going to be harder.”

Laskaris added students should be aware that colleges often use the waitlist to balance the incoming class profile based on numerous factors, including gender.

“The waitlist is an opportunity to very strategically admit students to hit an enrollment goal,” she said. “And if the goal is relative gender parity, then yes, you might use the waitlist for that.”

At MIT, where the yield hovers around 85%, few waitlisted students receive an offer. In the 2023 cycle, only 32 students out of a pool of 558 got in off the waitlist, and those figures aren’t broken down by gender, so it’s unclear if gender preferences prevailed. Nonetheless, that year, men outnumbered women by only 22 in the incoming class.

Perhaps Harvey Mudd, which accepted 53 of 403 off its waitlist in 2024-25, used that round to achieve almost perfect gender equity.

Yet Tulane, with its equally stingy waitlist, accepting 43 out of 2,168 in 2023-24, didn’t come close to accomplishing gender equity. Even if all 43 were male, it hardly put a dent in the imbalance of an incoming class featuring 1,190 women and 677 men.

Achieving gender parity on campus may be a more important strategic goal for some intuitions than for others, or maybe just a more achievable goal, and elite colleges striving to reach that balance are making necessary choices in the admissions process that favor one gender over another.

“Colleges have decided, and society has decided, that a well-rounded, highly diverse incoming class is a good thing, and colleges are going to do what they can in order to build that incoming class,” Weingarten said. “Diversity involves everything from race and ethnicity to geography, socioeconomic status, and gender.”