Food Insecurity Is Surging on College Campuses. Here’s How One University Is Helping Its Students

Credit: Image Courtesy of John Hancock

Credit: Image Courtesy of John Hancock- A recent University of Northern Colorado survey found 47% of students experienced some sort of food insecurity in the last year, the highest in university history.

- UNC’s Bear Pantry partners with local food banks and organizations and campus groups to provide food to students facing food insecurity.

- The community and volunteers at the Bear Pantry reshape the conversation about food insecurity. Students can share stories and challenges within the pantry.

- BestColleges reported college students who were food insecure were less likely to get their bachelor’s degrees in 2020 than those who were food secure (21% vs. 36%).

Hungry community members at the University of Northern Colorado (UNC) can always find food and a warm smile at the Bear Pantry.

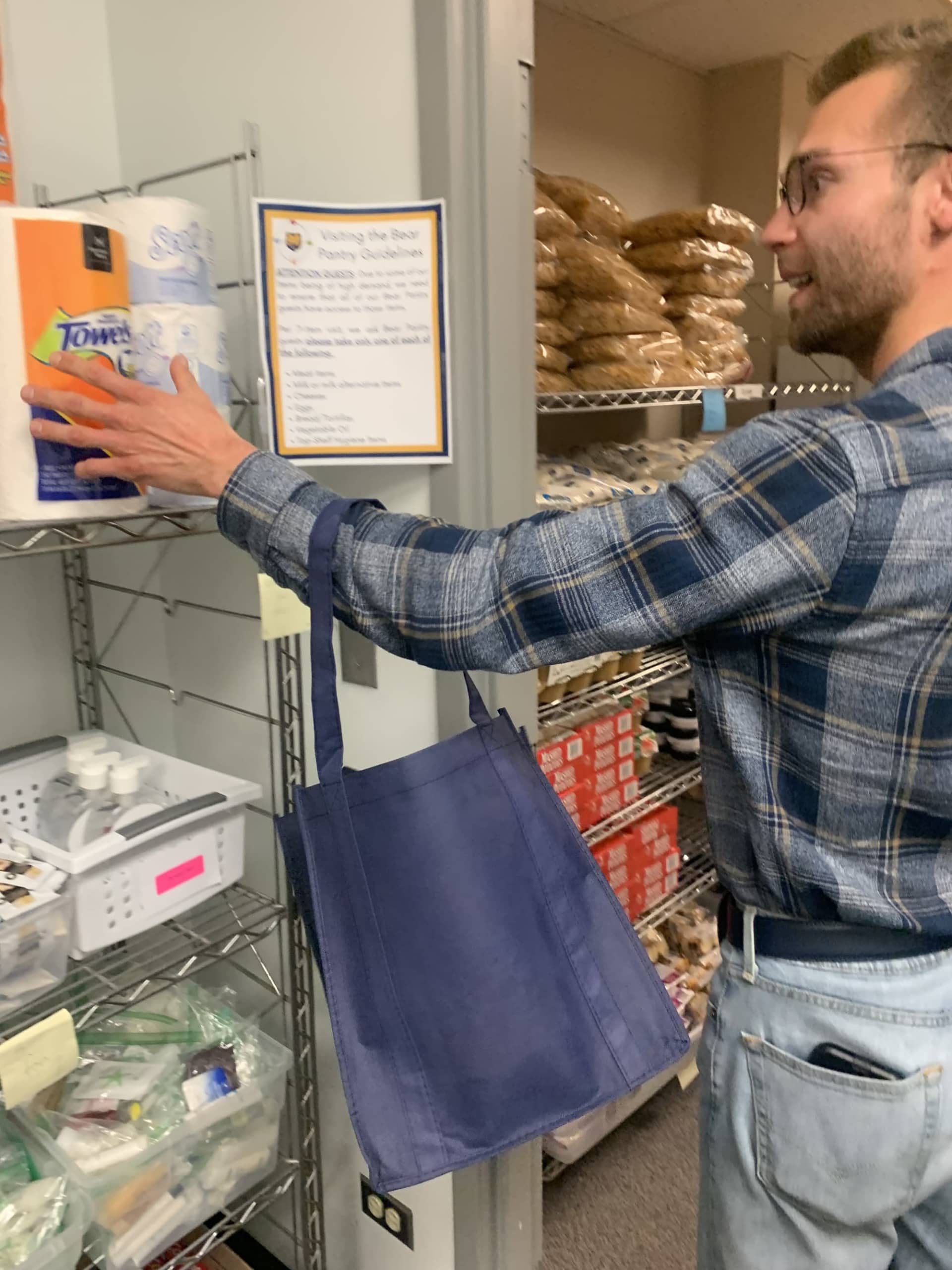

UNC’s Bear Pantry is one of several initiatives to fight campus food insecurity at the Greeley, Colorado, institution that enrolls some 9,000 undergraduate and graduate students. Any student, faculty member, or staff member can visit one time per week and get up to seven items at no cost. All community members need to do is have a Bear ID number and stop by.

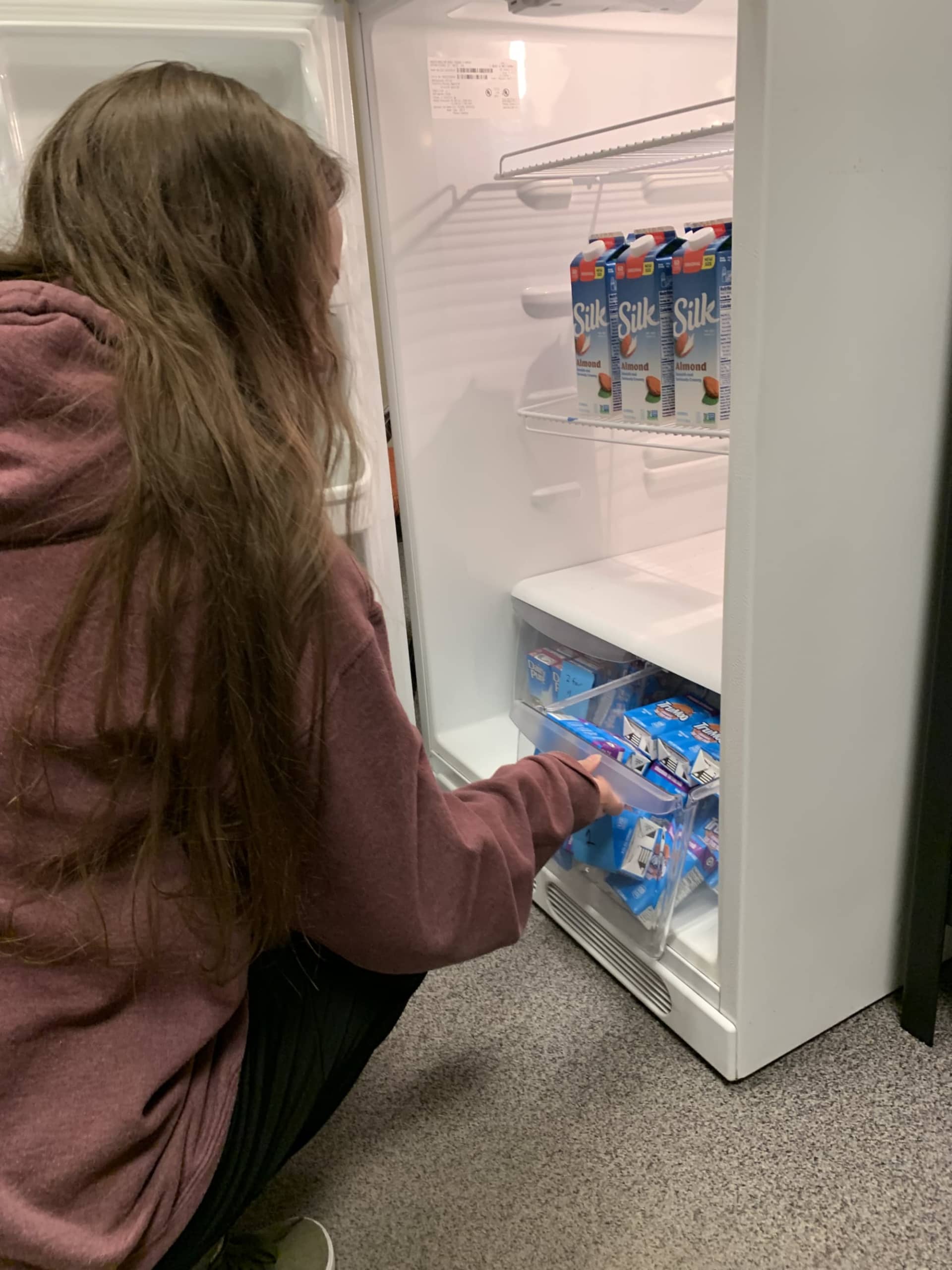

Now, the pantry is in the university center, lined with racks of nonperishables like mac and cheese, pasta, sauces, and canned goods, and other items like toiletries and bread. It’s open Monday through Thursday for about 15 hours a week for students, faculty, and staff.

John Hancock, assistant vice president for wellness and support, told BestColleges about 80 students recently came in during one shift. It, unfortunately, wasn’t a surprise to UNC, which though a recent student survey discovered 47% of students experienced some sort of food insecurity in the last year, the highest in university history.

UNC’s findings aren’t unique: Research by BestColleges also shed light on the growing nationwide problem of food insecurity among students.

Around 23% of college students were food insecure in 2020, the most recent year for which data is available, according to BestColleges. BestColleges also reported college students who were food insecure were less likely to get their bachelor’s degrees than those who were food secure (21% vs. 36%).

UNC is combating food insecurity in its community through a multi-pronged approach that includes the Bear Pantry, a meal-share program, and initiatives to change the language around basic-needs insecurity. The institution’s success may serve as a model for how other regional public colleges and universities can better support their students experiencing food insecurity.

Hancock was a psychologist before he started his new university position as assistant vice president for wellness and support. He said he’s always felt called to work with vulnerable populations through individual and systemic programs. He also has experience with grant writing, which has proved useful for the pantry.

“So it felt like a natural fit for me. But honestly, I took it, and I took the job because this was what I was going to have a chance to do.”

UNC’s Bear Pantry opened in the fall of 2014 in a room that could comfortably fit two people in the lower levels of one of the campus buildings. The pantry had no additional staffing or funding; the founders just wanted to feed students until someone told them to stop.

Since then, the pantry has garnered two important partnerships with the dining hall vendor and Weld Food Bank to give students free dining hall meals and food wherever they are.

Invaluable Partnerships to Fight Food Insecurity

UNC’s Bear Share Meals program awards a few students weekly dining hall meals.

Freddie Horn, a graduate student studying psychology, chose to do his assistantship at the pantry because there weren’t as many resources available to students facing food concerns.

“I knew as an undergrad how hard it was and how challenging it was,” Horn told BestColleges. “And I did an AmeriCorps term in Atlanta, and I worked with a lot of people during my AmeriCorps that faced food insecurity, and I myself did as well. So I wanted to be able to explore a different way to help people outside of the therapy room.”

Horn will sift through requests each week and award dining hall meals to a select number of students each week.

UNC can gift dining meals through a partnership with the university’s dining hall vendor and a system where students on a dining hall plan can donate up to three meals toward Bear Share Meals.

“We’re the Bears, and so we say once a Bear, always a Bear. And we also have this thing about ‘Bears give back,'” said Hancock. “So a lot of our students who are Bears and have extra meals on their dining cards can donate those to the pantry, and then we can give those out to students in need.”

The newest addition to the Bear Pantry is the mobile food pantry with Weld Food Bank.

The mobile food pantry is a refurbished, redesigned, and modified beverage truck that brings thousands of pounds of food the pantry doesn’t normally hold, like perishable refrigerated items, produce, and more. UNC hosts the mobile food pantry about once a month.

“Students were leaving that event with four or five bags of groceries with melons and produce and ground beef and eggs, and it was just an amazing event,” Hancock said.

The largest contributor to the pantry is the Weld Food Bank. Every Monday, Horn restocks the Bear Pantry by ordering and picking up food from the food bank and local grocery stores. Students will donate individually, and the university, clubs, fraternities, and sororities will donate leftover food and hold donation events.

University employees also have the option to enroll in an automatic payroll donation to the Bear Pantry. If they choose, the university will deduct an amount from an employee’s paycheck to give to the pantry.

Students Know About the Bear Pantry

“Based on the turnout for recent events, I’d say students, a high number of our students, know what we’re about and what we’re up to, and they take advantage of [the food pantry],” Hancock said.

In fact, students learn about the pantry as soon as they walk on campus. During new student orientations, representatives of the Bear Pantry are front-and-center, letting students know about the pantry and how to get involved by tabling around campus.

Horn is responsible for putting out Bear Pantry awareness and volunteer opportunities in e-newsletters. Students can also find information on faculty syllabi if faculty choose to include resources on student well-being.

The pantry will typically have two volunteers at a time: one to greet students at the door and another to help students check out pantry items and talk with the students about additional resources on campus.

“Ultimately, we want people to feel welcome when they come in,” Horn said. “We orient our Bear Pantry around a sense of community, so just interacting with all of our students, making sure it’s stocked, and everyone’s feeling welcome.”

Taylor Schiestel, director of student outreach and support and soon-to-be head of the Bear Pantry, remembers seeing the closet-like Bear Pantry when she went to UNC and nobody knew what it was.

“I am a ride-or-die for Greeley[,Colorado] and for UNC. Both my parents are alumni, I’m alumni,” Schiestel told BestColleges. “And then I just love the connection that the Bear Pantry brings and the connection with my community. And I like to say what a better way to connect through food.”

Why Is There Food Insecurity on College Campuses?

Hancock said UNC prides itself as a place that supports social mobility. A significant percentage of UNC’s students are first-generation college students, and many are eligible for Pell Grants.

First-generation college students in the U.S. who were food insecure finished college at a significantly lower rate than those who were first-generation and food secure (47% vs. 59%), according to BestColleges.

“Here at UNC anyway, we do have a population that, on average, is going to tend to be a little more challenged with food security issues generally just because of their socioeconomic makeup,” Hancock said.

The rising cost of college also contributes to food insecurity. According to BestColleges, attending a four-year public college costs 64% more than it did 20 years ago, and attending a two-year public college costs 59% more than it did 20 years ago.

“So what’s a student to do in terms of trying to keep up with the expenses?” Hancock asked. “And this is true if it’s just you, but imagine now if you have a dependent that counts on you, a child, in terms of how are you going to pinch pennies and try to make all this work.”

Hancock said data shows an intersectionality around historically excluded identities and food insecurities. Students can feel pinched when they have lots of forces working against them.

Students also may not have the means to go to the grocery store.

“Our campus isn’t too far from grocery stores, but if you’re going to be trying to get groceries and bring ’em back to a place you live on campus, it’s a bit challenging,” Hancock said.

Horn said one of the biggest challenges to students facing food insecurity on campus is the stigma and shame associated with getting help, whether it be food, affordable housing, or mental health services.

A mission for the pantry is to change the language around getting food. The pantry aims to create a warm and welcoming environment where students, staff, and faculty do not feel ashamed to get food.

“And that’s by having amazing volunteers here every single day that the Bear Pantry is open, establishing community events where people can donate to us and feel like they’re contributing to something greater,” Horn said.

What Can Colleges Do to Help Students?

Keeping costs down is the No. 1 thing colleges can do to help students, Hancock said. Doing so benefits the institution in determining how to run the university more efficiently, which lowers the amount students have to pay in tuition and fees.

But institutions also need to regularly survey students on the levels of food insecurity they experience, he said.

Talking about college student food insecurity is the starting point for combating food insecurity on campus, Hancock said.

“The more we discuss this challenge and how to meet it, the better prepared we can be.”

Universities can also follow in UNC’s footsteps by writing grants and developing partnerships with local food pantries, organizations, and dining vendors.

Tapping into volunteer opportunities and partnerships is critical to the Bear Pantry’s growth, which is looking to expand by 2025, Hancock said.

The team wants to expand the Bear Pantry into a bright and welcoming storefront 3-4 times the size of the current one with produce and an online ordering system in the student center. Hancock wrote a grant last spring to do a significant renovation in the student center, set to finish by January 2025 or earlier.

Hancock said the goal is to enable online ordering where students can pick up their food from lockers after hours.

UNC is also planning a neighboring student well-being hub, where students can get additional resources and apply for things like SNAP benefits.

“So it even gives a warm handoff to those students who come in and need more resources and having our volunteers and our students be able to walk them over so they can get resources right then and there, making that even more accessible,” Schiestel said.

Schiestel said the beauty of the Bear Pantry is in the stories, challenges, and experiences told within its walls.

“Just coming in brand new and just witnessing the beauty of friendship blossoming in Bear Pantry, the beauty of just connection and knowing that students are not alone with what they’re facing has been something that’s just super beautiful,” she said.

“And every person that comes through the Bear Pantry and every volunteer that talks to a student coming through the Bear Pantry respects and acknowledges what specific challenges and hardships and what stages of life everyone is in, which is kind of, it just makes what we do so much more meaningful to have students know that they aren’t alone in that process.